Psychoanalysis is developed by Sigmund Freud beginning in the 1890s as a method of treating patients with psychological problems. Although contemporary psychology has largely rejected Freudian methods as unscientific, psychoanalysis gained new life in the middle part of the 20th century as a tool for cultural criticism.

Repression and Monsters

This makes sense for a number of reasons. Much of the criticism of Freud comes from his evidence. He builds his theories based on analytic sessions with patients, but also from mythology, religious ritual, art, drama, literature and history (Freud, 1961 [1930]; Gay, 1989). He builds a theory of the mind based on cultural evidence. Perhaps his theories are better suited to the fields from which he draws evidence. Perhaps he is a keen observer of cultural process. His foundational text in establishing psychoanalysis is his mammoth The Interpretation of Dreams (1965 [1901]). His central thesis is that dreams are the fulfillment of wishes. This makes sense for good dreams. But in explaining how bad dreams can also be things we wish for, he outlines the process central to all psychoanalysis, and in so doing, he gives us a glimpse as to how and why we should use his ideas for popular culture analysis:

We may therefore suppose that dreams are given their shape in individual human beings by the operation of two psychical forces . . . and that one of these forces constructs the wish which is expressed by the dream, while the other exercises a censorship upon this dream-wish and, by the use of that censorship, forcible brings about a distortion in the expression of the wish. (p. 177)

We don’t experience our wishes simply, because parts of our minds get in the way. This is exactly the experience of entertainment. There are things we wish for (happy endings), horrible things we wouldn’t want but we seem to like watching on the screen (the Saw movies, for example), and a variety of strange things that are hard to explain.

For Freud, we are creatures of desire, a part of us he calls the id. But the id wants animalistic things like food, sex, violence and various pleasures. And we all grow up in a society that teaches us morality which forbids some of that. This becomes the superego, the voice of the moral order. That superego tries to repress those “sinful” desires. The other part of our self is the ego, or the rational seat of our self concept. It must decide actions based on weighing desire versus morality and make other judgments about things like what is feasible, affordable or what we can get away with. As a result of all of these processes, various desires we have are repressed into the unconscious, or the “place” where all of the memories and ideas we have that we are not currently aware of exist.

So, moving back to dreams, where unconscious processes can take place, given that our willful consciousness is asleep, sinful desires that we wish for are transformed into symbols in order to get by the superego. This way we can wish for things that we “shouldn’t” wish for. And in the midst of “good” wishes, the repressed will rise up as, perhaps, a monster. As to the other process, the monster, what Robin Wood (1984) calls “the return of the repressed” (p. 173), comes out in the collective nightmares of horror movies and scary moments in other films. For Carol Clover (1992), the monsters in horror films represent all sorts of fears and issues, from gender identity to religious doubt to existential angst. In Jancovich’s (1996) study of 1950s monster movies, fears of nuclear war transmuted into giant radioactive lizards and insects. The unspeakable can only become speakable when it transforms. Hippies (The Last House on the Left) and babies (It’s Alive) kill us in the 1970s, family kills us in the 1980s (The Stepfather), etc.

Whether or not any of this happens in “real” dreams and people, both processes seem to happen in popular culture. And what is popular culture other than a theater of our dreams?

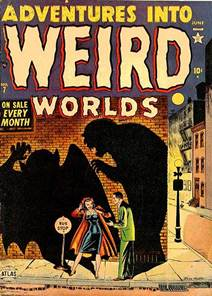

This cover image of a horror comic shows some of the importance of these ideas. First, horror filmmakers and directors like Hitchcock incorporated a variety of different psychoanalytic concepts into their films on the 1930s and 1940s very explicitly, so at a very simple level, the influence of this cannot be simply ignored. At a deeper level, there are many emotive genres of storytelling where questions of the repressed and the emergence of those repressed desires are key.

Hitchcock’s Spellbound and Psycho and Vertigo and Marnie articulate this rather pedantically.

Many horror tales have monsters which are a version of repressed desire coming to the surface, like Dr. Jeykll and Mr. Hyde or Black Swan. And there's always the big green rage monster:

She is immortal and lonely. But whenever she finally has sex with someone, she can’t stop herself from killing them, which almost happened to Edward in Breaking Dawn.

Here is what happens to Simone Simon’s character in Cat People when she feels romantic:

It’s not always this simple, though (didn’t you just know I was going to say that?)

Displacement

In a horror movie the repressed bursts, uncontrolled, because the fictional world allows for it. This is not always the case. In dreams or popular culture where there is still an operative morality that would prevent it, the repressed returns in a different, more hidden form. This symbolic slippage where desires show up in other forms, which Freud (1965 [1901]) calls displacement, shows up in a variety of ways. Most commonly we end up looking for representations of sexuality or violence that are hidden or obscured. These are fetishes, or objects that stand in for something which our superegos repress. In a Hollywood and television system filled with censorship, we can see this happen rather deliberately, but it happens unconsciously on the part of producers, as well.

Here’s some oral fixation moments from To Have and Have Not:

In this case, the cigarette stands in for sex. There are plenty of other ways sex is displaced onto other forms. The prevalence of the phallic symbol in censored media when characters are not allowed to act on their desires is common.

Here’s North by Northwest again:

That power is often translated into violence. When women are killed in horror films, almost always by a penetrating knife, the sounds they make are more akin to the sounds of desire in a porno flick than actual screams of pain and horror. And in many porno flicks, the sex is violent and dehumanizing and not entirely about sexual pleasure as much as it is about power and violence. This slippage is possible because both are repressed into the cauldron of the unconscious. It is also possible because of the working of the primal scene, which, for Freud, is the moment of seeing someone (often your parents) having sex for the first time. It is confusing, often glimpsed or heard with barriers to perception (through a keyhole, heard from across the house, etc.). It is often not possible in those stressful moments to know what is happening. And if sex is a new concept, perhaps the only way to first make sense of it is with notions of violence (“They are wrestling” and “I didn’t want him to hurt my mom” are two experiences students have shared in my classes).

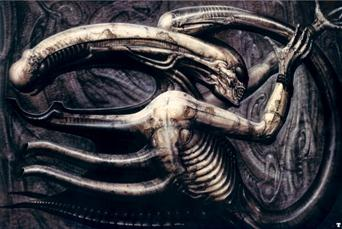

In a film like Alien, the monster rapes people’s faces, emerges in a monstrous pregnancy, grows into a giant phallic-headed demon, where it stabs you with its extra erection:

This creature design comes from a particular set of special effects design, from H.R. Giger, which is already a huge mix of sex and violence. Here's a relatively tame one:

In North by Northwest, we have the following dialogue between the romantic leads:

Eve Kendall: How do I know you aren't a murderer?

Roger Thornhill: You don't.

Eve Kendall: Maybe you're planning to murder me right here, tonight.

Roger Thornhill: Shall I?

Eve Kendall: Please do.

How about Punch-Drunk Love?

The Uncanny

Freud’s idea of the uncanny is the idea that some repressed fear, something which we experience as unfamiliar, is both secretly familiar and seemingly old and primitive (Hutchings, 2004; Wells, 2000). For Freud it almost seems as if this is a special sort of feeling that comes from some degree of self-knowledge that the repressed is emerging, and it feels like a long lost and very ancient and horrible thing. This is the way memory works in texts like The Shining and many ghost movies. It also seems to be a part of the idea of mental breakdown as a result of horror, as in Lovecraft’s cthulhu stories and the old gothic novels.

At a simple level, this idea is in popular discourse as the “uncanny valley” of digitally animated humans. It is the same question of how the familiar and unfamiliar cue each other. We are reminded of the structures of repression and displacement. And it disquiets us. It is as if we don’t really know ourselves or what we are capable of. It’s why most gothic era ghosts stories ended, not in death, but in insanity.

The Abject

Julia Kristeva’s (1982) idea of the “abject” is a furthering of this. If the uncanny is a process that reminds of us the frailty of our sense of self, if it reminds us that the illusion of your “self” as a whole person is an illusion, the abject is a sometimes parallel crisis of the body.

The abject is a visceral rejection and disgust of things that emphasize the body and the borders, edges and chaos possible for the body. For Kristeva, we develop our self, which is kind of an illusion, by gathering forces of “non-self” and expunging them. Gore, zombies, and films like The Fly, where Jeff Goldblum is merged with an insect in a scientific accident, emphasize this. Of course, these things are still often desired, just as the uncanny are desired in clown horror movies. We want and need these kids of monsters. Perhaps popular culture helps us work through anxieties we already have. Perhaps desire for this stuff is some kind of displacement.

But we seem to want it. Or, at least, we want to watch other people go through it.

We are haunted by our deaths. We are repelled and fascinated by it. And as with the uncanny, we have a particular set of tales about the cost of looking, for the character.

Conclusion

The key things to take away from psychoanalysis are the mechanisms of repression and displacement and the thematics of sex, violence, death and fear. Any and all of these anxieties and desires can commingle, especially in genres, like horror, where the difference between anxiety and pleasure is, as perhaps in dreams, not always clear.

By Steven S. Vrooman, Revised July 2024

References

Clover, C. J. (1992). Men, women and chainsaws. Princeton: Princeton UP.

Freud, S. (1961). Civilization and its discontents. New York: Norton.

Freud, S. (1965 [1901]). The interpretation of dreams. New York: Avon.

Gay, P. (1989). Sigmund Freud: a brief life. In J. Strachey (Ed.), Beyond the pleasure principle (pp. ix-xxiv). New York: Norton

Hutchings, P. (2004). The horror film. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Jancovich, M. (1996). Rational fears: American horror in the 1950s. Manchester: Manchester UP.

Wells, P. (2000). The horror genre. London: Wallflower.

Wood, R. (1984). An introduction to the American horror film. In B. K. Grant (Ed.), Planks of reason. (pp. 164-200). Latham, MD: Scarecrow.

No comments:

Post a Comment