We're talking about race and racism here and how it connected with media and popular culture.

“Race”

“Race” theory analyzes the ways in which racism works in society and in

popular culture. The most important concept here is race itself.

As Stam (2001) argues, there is “an emerging consensus within various

fields” that “race” doesn't exist: “There is no race, then, but only racism”

(p. 477). So from the 80s through the early 2000s the term race is often in

quote arks like that, to mark it as something we should be critical of.

Of course we have biological differences as people, but only some of

those differences count as race, and it's pretty telling what those are.

Different hair colors, for example, are not considered as important in defining

a person's race as other characteristics like the color of their skin. Whether

or not ears are attached at the bottom of the lobe or not is generally not

considered something that defines a person's race, whereas the shape of

someone's nose or eyes often is. What's going on here?

Lively’s (2000) review of the history of the development of the idea

of “race” is telling. Race is generally thought to be invented only a few

hundred years ago, and certainly by the time of the enslavement of Africans,

the first people enslaved because of their race. History is full of conquering

people enslaving the people they vanquished, but with African slavery, various

peoples or nations are united conceptually under the category of Black and

enslaved, and not as a result of a war victory, either, but with a spreading

colonial machine of the slave trade. Eventually, under the nineteenth century’s

pseudo-scientific discourse of social darwinism, folks first began to

think of people as separated into various races, which were then often

hierarchically sorted into superior and inferior.

So the invention of race as a meaningful concept is fraught with all of

this. Race was an idea that helped some people diminish others. As time has

gone on and we have accepted it as a "fact" of humanity, we have

accepted large swaths of such old ideas unproblematically for much of American

history.

And because so many of those definitions of race existed in order to

identify if someone was not white in order to levy various kinds of racist laws

or practices, definitions of race for multiracial people have long been strange

and illogical. For example, for much of US history there was a semi official

legal structure called the “one drop rule”

that specified that anyone with a Black ancestor was considered Black for the

purposes of various kinds of legal issues, from employment to divorce. The

purpose of that particular definition of race was to levy social and legal

power, not to identify people with any sense of accuracy or care.

All of this is important for thinking about race in media because

narratives can participate in these logics or challenge them, but without

knowing the history, it is sometimes hard for a student to notice what, if

anything, is happening in the text.

Racisms

All of what we’ve explored so far are foundational parts of the development

of what is eventually termed “critical race theory,” but it is not the whole

story. Right wing opposition to the idea that this would be taught in schools

stems from the implications of these ideas in practice.

From the perspective of an everyday person who knows little about race

theory, for example, if I call you a racist, you are likely to be very offended.

It’s sort of a terrible and convenient trick that calling someone racist is

considered offensive or mean and not a statement of fact to be judged.

There are many reasons for that, but one is that people tend to define

the idea of racism as active hatred by a person for another. So, if they don’t

feel like they feel such hatred, they can’t understand how they can be a racist.

And critical race theory has an answer as to how, and folks don’t like that.

As critical race theory becomes more

well known and simplified, the picture of racism is one of levels, as

demonstrated on the website of the National

Museum of African American History & Culture.

Individual racism is composed of our beliefs and actions. Interpersonal

racism is composed of acts toward another. Institutional racism is

how larger structures work in racist ways and are structured on racist

practice. Structural racism is how the interrelationship of those

institutions is similarly enmeshed.

So even in this picture you can see

why there is resistance. The idea that a person who may not have actively

racist thoughts or engages in actively racist actions can be working toward

racist ends by participating in institutions and structures that are constituted

by racist practice and continue to do so is really disturbing to those who believe

that all that matters are an individual’s thoughts and feelings!

But it’s more complicated that that.

We talk about the idea of “implicit bias,” or the ways that we are affected by

unwilled prejudices. And then I might interpersonally interact in ways that

express those, again, without knowing, perhaps. So that’s another level in

which we might be a part of the picture of US racism.

Another way to talk about bias is by

breaking racism down in another way. Stuart Hall (1981) identifies what he

called overt racism and inferential racism, and I think those

terms are helpful to think about. We might call these the two pieces that are

the deep structure or implicit bias (which may be conscious or not).

Overt racism is composed of beliefs

that explicitly attribute behavior to racial identity or difference as a causal

factor, which is kind of the basic definition of racism. If I think you do

behavior X or are good at behavior Y or are bad at behavior Z because of your

race, that is overt racism, even if I am not aware that’s what I am thinking. Note

that we think of racism as hate, but that’s not what this is. This is the

intellectual assumption that there are biological racial differences that determine

behavior in others.

Inferential racism, for Hall, is the often

unthinking acceptance of the results of overt racism. For example, it was well

known through the 90s that news reports of crimes would often only identify the

race of a suspect if that suspect was not white. Was this thoughtful or as a

result of inferential habit? It just didn’t occur to the news readers to say

things like “a white male in his 30s . . . “ etc. If you asked them they might

even be horrified they were doing that, but that’s how implicit boas works, an

inference of racism.

For example, having red

hair once marked you as being more prone to criminal behavior. Sure, there are

plenty of hair colors for the Irish, but that red color was somehow the worst. My

family was Irish enough on one side that we had these ideas and it was just

kind of understood that the redheads in the family were faster to anger. At a

kid my hair was a lot of colors, ranging from blonde to red to brown. When I would

have an angry childhood or teenage outburst at some point, you could almost

guarantee that the next day someone would offhand mention that my hair was looking

a bit more red than it used to. And it seemed like this was not a joke!

Police vans were called “Paddy

Wagons” after the Irish they’d arrest. A common saying, also in my family, if

you did something wrong was that a mom or dad would “beat you like a red-headed

step-child.” The echoes of this are in contemporary anti “ginger” play/performative racism.

So you can see it all

building up into habits, sayings, cliches, and bits of things on TV. Media

becomes a part of this larger process. Institutional and structural racisms are

grounded in this way, and often they are talked about as systemic or systematic

racism. As Stam (2001) defines it: “Since racism is a complex hierarchical

system, a structured ensemble of social and institutional practices and

discourses, individuals do not have to actively express or practice racism to

be its beneficiaries . . . In a systematically racist society, racism is the

'normal' pathology, from which virtually no one is exempt, including even its

victims” (p. 477).

Essentialism

& Stereotype

How does this work in

terms of media? Sure, entertainment texts can be about race issues and history,

but often they are products of racist logics, a well, especially given the

structural inequities behind the camera.

So we get to what we might

call, inspired by Stuart Hall, overt essentialism and inferential

essentialism. Essentialism is a kind of emotional, symbolic or

representational racism. It’s the idea that there is some essential quality or behavior

associated with the physical characteristics of a racial identity.

Entertainment often represents race in ways that are awash with this, even

today.

Overt essentialism is

clearly racist and easy to spot, at least in retrospect.

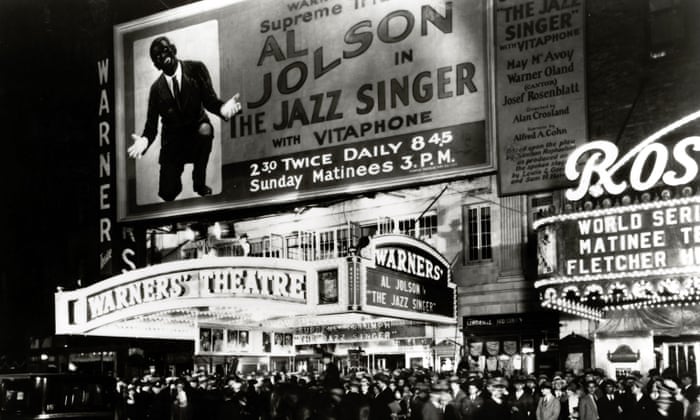

Hollywood, for example, had a long history of blackface, for a variety of terrible reasons, of white actors in makeup, including the first talkie motion picture, The Jazz Singer in 1927:

Aside from all the obvious things wrong with this kind of thing, the more subtle element comes from the way the symbolic logics of racism transcend the practice. Although blackface is mostly over in film, we see versions of it with white actors made up to be Latinx or Asian American up until fairly recently.

But blackface portrayals had this element of essentialism to them.

The person changed through putting on the makeup in the story of the films. So

that when blackface goes away, it really also doesn’t.

1986’s Soul Man, when a white student overdoses on tanning pills so that he can try to take an affirmative action scholarship to Harvard Law School, blackface returns for the newly conservative Reagan era. Although he begins his days as a pretend black man in awkward situations, bad at basketball and women, he of course becomes excellent at both. Apparently it rubbed off on him?

Because we’re talking about actors pretending to other races, it

is easier to see what essentialism is. Soul Man is overt essentialism.

Skin color = basketball.

But inferential kinds of essentialism are more common. The “hot

Latin lover” goes all the way back to Valentino in the 1920s:

Asian characters in films continue to be good at martial arts. In the 80s, it was always cameras, as well, as in The Goonies:

There is a long history of Black characters in early films being “naturally” servile, especially in the mammy figure, who just loves taking care of white kids, and the actual character Mammy from Gone with the Wind, who loves it so much she stays serving her masters after slavery ends:But it is not just stereotypes of other groups. We often use essentialism as a kind of pride within a group, and that’s where it gets complicated. LaGrone’s (2000) history of gangsta rap talks about the appeal to white teens of the gangsta character and how that character in rap music supplanted early, more “authentic” rap by artists like Afrika Bambaataa because the thug image in groups like N.W.A. were more popular with white kids, who were always the majority audience for rap music (a minority of white kids in the 80s liked rap, but even that minority was larger than all other groups of rap fans combined, included Black teens). Thus the business incentivized artists to sell themselves as thugs and rewarded them for that in many ways.

Thus, various essentialisms, which often contradict are present

over time as the system rewards those portrayals. Almost always this is because

it is what the audience wants and entertainment tends to follow the money and

follow the trends.

Color

In various forms of racism, questions of color take on specific

sets of meaning that interact with essentialism but which also have different

sorts of meanings and implications. The further away from a perceived norm of

whiteness a person is, the more they might embody an essentialist stereotype,

as if the two varied together. But, paradoxically, the closer a nonwhite person

is to a racist white ideal, the essentialisms will be represented as stronger

as well. This seeming paradox has different elements.

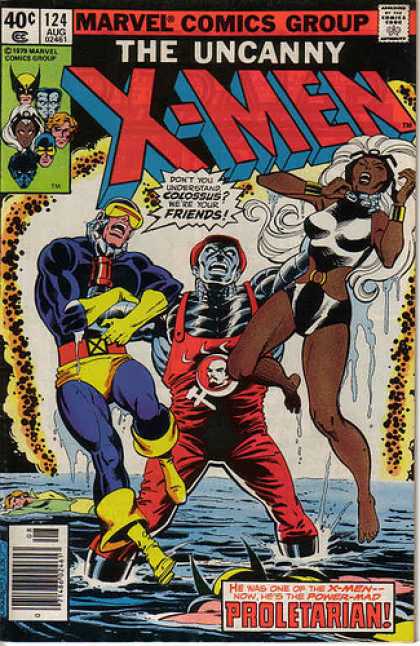

X-Men’s Storm, for example, an African Princess/Queen, is played by an actress with lighter skin tones and different kinds of facial features in the films:

But at the same time, lighter skin is often associated with

negative stereotyping as well. In this case, we shift to a racism that is based

more heavily on fear.

A classic racist fear is

of “miscegenation,” which is interracial procreation. The

idea of a mixed race person is disturbing for a structurally racist state,

which is why rules like the aforementioned “one drop rule” existed, to exactly

define the boundaries of race (to all the more pretend it is clear and real and

should be the source of domination in the law?).

Anderson (1997) chronicles the tragic mulatta and the jezebel figures

as the only other two typical representations African American women in the 20th century

besides the Mammy.

The first, the tragic mulatta, is a mixed-race woman who attempts to pass for white. Her innate inferiority eventually affects her attempts and she is destroyed. This is the case in 1949’s Pinky:

In texts like these, Hollywood tells cautionary tales about people whose existence defies the racist structures.

Conclusion

Thus racisms and essentialisms

have many different forms.

There is plenty more to

say on these issues, including the history of the portrayals of whiteness,

symbolic annihilations and erasures, as well as tokenism as these things

begin to change.

Tokens are characters who

show off some superficial diversity without having as meaningful a story arc as

the white characters. There’s lots of examples and lots to talk about there,

but we will do that in class, as you are all likely more familiar with that

space.

by

Steven Vrooman

1998-2023

References

Anderson, L. (1997). Mammies no more. Rowan and

Littlefield.

Hall, S. (1981). The whites of

their eyes. In (G. Bridges and R. Brunt, Eds.) Silver Linings. Lawrence & Wishart.

LaGrone,

K. (2000). From ministrelsy to gangsta rap: The “Nigger” as commodity for

popular American entertainment. Journal of African American Studies, 5,

117-131.

Parameswaran,

R., & Cardoza,

K. (2009). IMMORTAL COMICS, EPIDERMAL POLITICS. Journal of Children & Media, 3, 19-34. http://bulldogs.tlu.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ufh&AN=36294559&loginpage=Login.asp&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Stam,

R. Cultural studies and race. In T. Miller (Ed.), A compansion to

cultural studies (pp.

471-489). New York: Wiley. http://books.google.com/books?id=HUl68Q9K6QwC&lpg=PA471&ots=G5bvsp6VSX&dq=robert%20stam%20cultural%20studies%20and%20race&pg=PA471#v=onepage&q=robert%20stam%20cultural%20studies%20and%20race&f=false

No comments:

Post a Comment